Starring a young blind girl trying to reach her parents’ home in the middle of a war, DeLight: A Journey Home aims to tell a story from a perspective rarely seen in games. As of this writing, only the first two chapters are available, so I cannot judge DeLight as a complete product. Having said that, the content released so far is impressive enough to leave me wanting more, for better and worse.

DeLight is a story-driven experience, so the gameplay mechanics mostly take a backseat here. Thankfully, the first two chapters largely succeed in telling an emotionally-gripping narrative. One of the most initially surprising aspects of the story is its tone. Despite its dark subject matter, DeLight has a mostly lighthearted feel to it, which is largely due to the simple art style and the laid back activities that the protagonist participates in. While the tone may seem ill-fitting at first, it ultimately just about works. These more low-key elements lull the player into a false sense of security, and they make the more emotional and suspenseful moments hit that much harder. Although dialogue takes up the majority of story sequences, the game features some notably strong sequences that tell the story largely through gameplay. For example, the sequence in which the girl has to follow her grandfather through the increasingly hostile town streets is incredibly effective at building tension not just because of the dialogue, but also because of the protests, guards, and fleeing citizens that players will naturally come across as they control the girl. Moments like this really stuck with me during my playthrough, which is exactly what a story-centric game like this needs to accomplish.

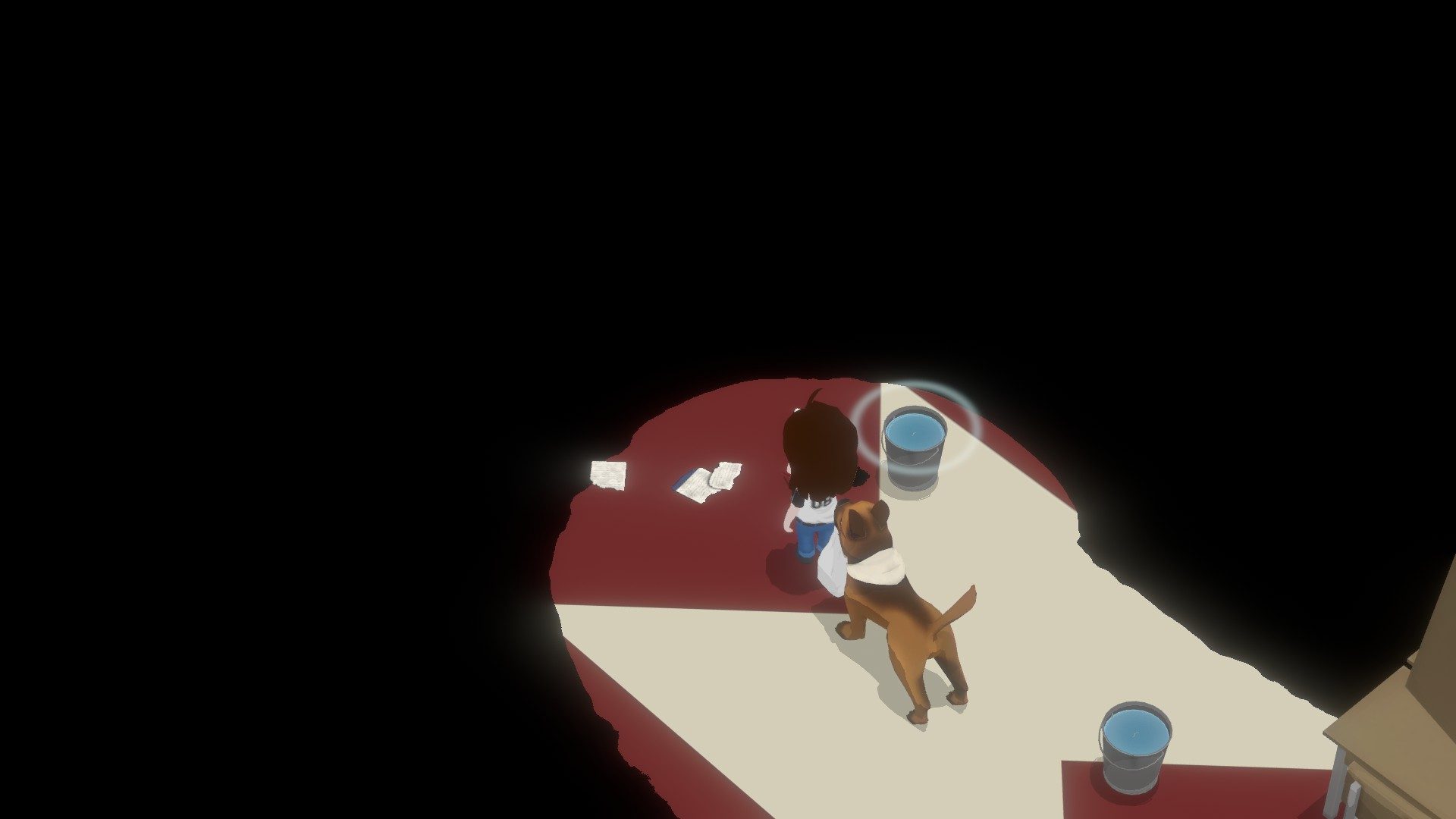

The story may be the highlight, but DeLight also crafts interesting gameplay mechanics to reflect the condition of the player character. Because the girl cannot see, the majority of the screen starts out pitch black, with the player only able to see the area immediately surrounding the girl. As the player moves around, more of the environment starts to become visible, with obstructions and characters in particular only revealing themselves when the girl brushes against them. Players essentially have to “feel” their way around the environment to learn its layout, which makes it a novel way to force players to think from the girl’s perspective. The game really takes advantage of these limitations through a few dedicated stealth segments which, while simple, are made more engaging thanks to the player’s limited visibility and the various obstructions peppered throughout. For me, the highlight of the gameplay comes when the girl receives her cane in Chapter 2. The cane extends the player’s visibility slightly, and the girl is trained to move around the room without bumping into objects. Players are told to move the stick left and right after each step, which actually reveals nearby obstructions slightly earlier than if they simply move around as normal. This stick strategy evokes the feeling of moving a cane to learn the environment around me, an effective move by the developers. The section itself may be brief, but it makes me appreciate the thought that went into the gameplay mechanics, which make the challenges the girl faces feel that much more real.

Although I appreciated the gameplay overall, I couldn’t help but think what my experience would have been if I were blind myself. Thinking from that perspective, DeLight is a huge wasted opportunity. The game makes note of the girl’s heightened senses resulting from her blindness. Unfortunately, the cues the game uses to represent these are almost all visual; soundwaves are evidently used to indicate noisy areas or objects of interest, but rarely do these make any sounds audible to the player. When the game does use actual sounds, they end up being entirely binary. Either the sound plays or it doesn’t. There are no dynamic sounds systems to indicate how close the player is to an object. Controller rumbling could have been implemented to indicate when the player touches an object, but since players are expected to configure the buttons if they wish to use a controller, that feature is also completely absent. Perhaps most crucially, since the dialogue is communicated entirely through text, gamers who are blind will have to rely on outside sources if they wish to experience the story. Granted, these accessibility concerns are far from trivial to address. Hiring voice actors and implementing dynamic sound design takes time and resources, and since DeLight was made with mobile devices in mind by a small team of developers on a limited budget, it is possible that the developers considered all of these accessibility concerns and simply weren’t able to address them. Even so, considering its premise, I would have loved to have seen DeLight really go out of its way to appeal to blind gamers around the world.

The game also contains some notable technical hiccups that I mainly found in Chapter 2. After leaving a room, two separate musical pieces started playing at the same time, which seemed to be fixable only by restarting from the last save point. I also encountered a situation in which I could not interact with an object needed to progress the story, forcing me to once again restart from the last save point. It is worth noting, however, how much the developers seem to be improving with experience. Dialogue in Chapter 1 seems stilted due to the lack of contractions, but Chapter 2 thankfully starts using them. The team is also regularly ironing out bugs as indicated on the game’s Steam page. These improvements give me hope that the developers will address at least some of these issues and make Chapters 3 through 5 truly worth remembering. I really enjoy what they have put out so far, so here’s hoping the final product truly hits home.

Score: 7 out of 10

Reviewed on Windows 10 PC

Play games, take surveys and take advantage of special offers to help support mxdwn.

Every dollar helps keep the content you love coming every single day.