In a more obscure corner of video game news this week, a retro 90s-style computer game has dropped in promotion of author Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, a novel releasing on July 5. Though the program, called Emily Blaster, is no AAA title, its use as marketing to promote the release of a book is quite inventive. Books have often been used to promote video games, from the countless Minecraft tie-ins we’ve all seen at Target to many simpler informational books released alongside games to ensnare younger readers. However, this is rarely (if ever) seen in reverse.

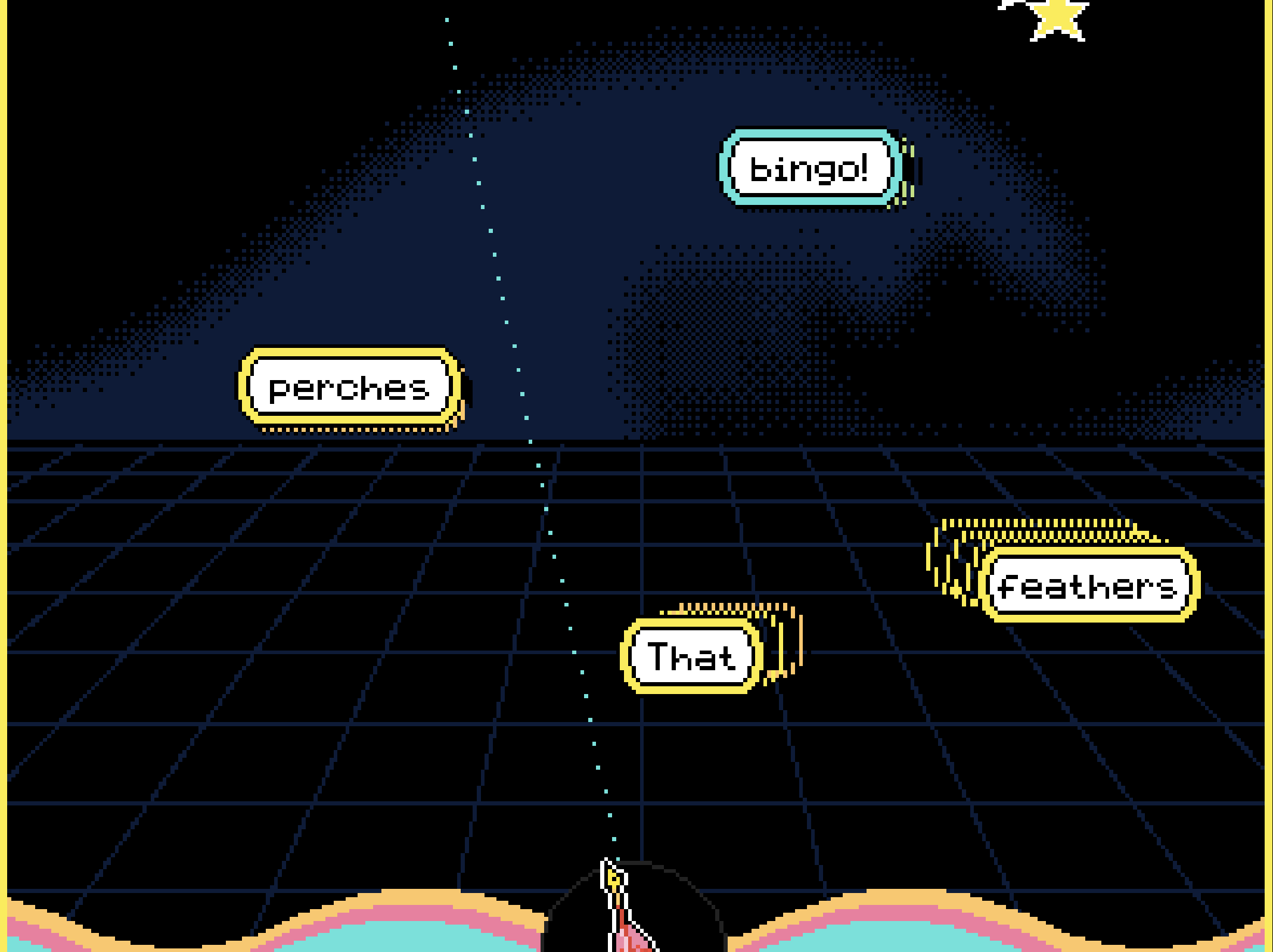

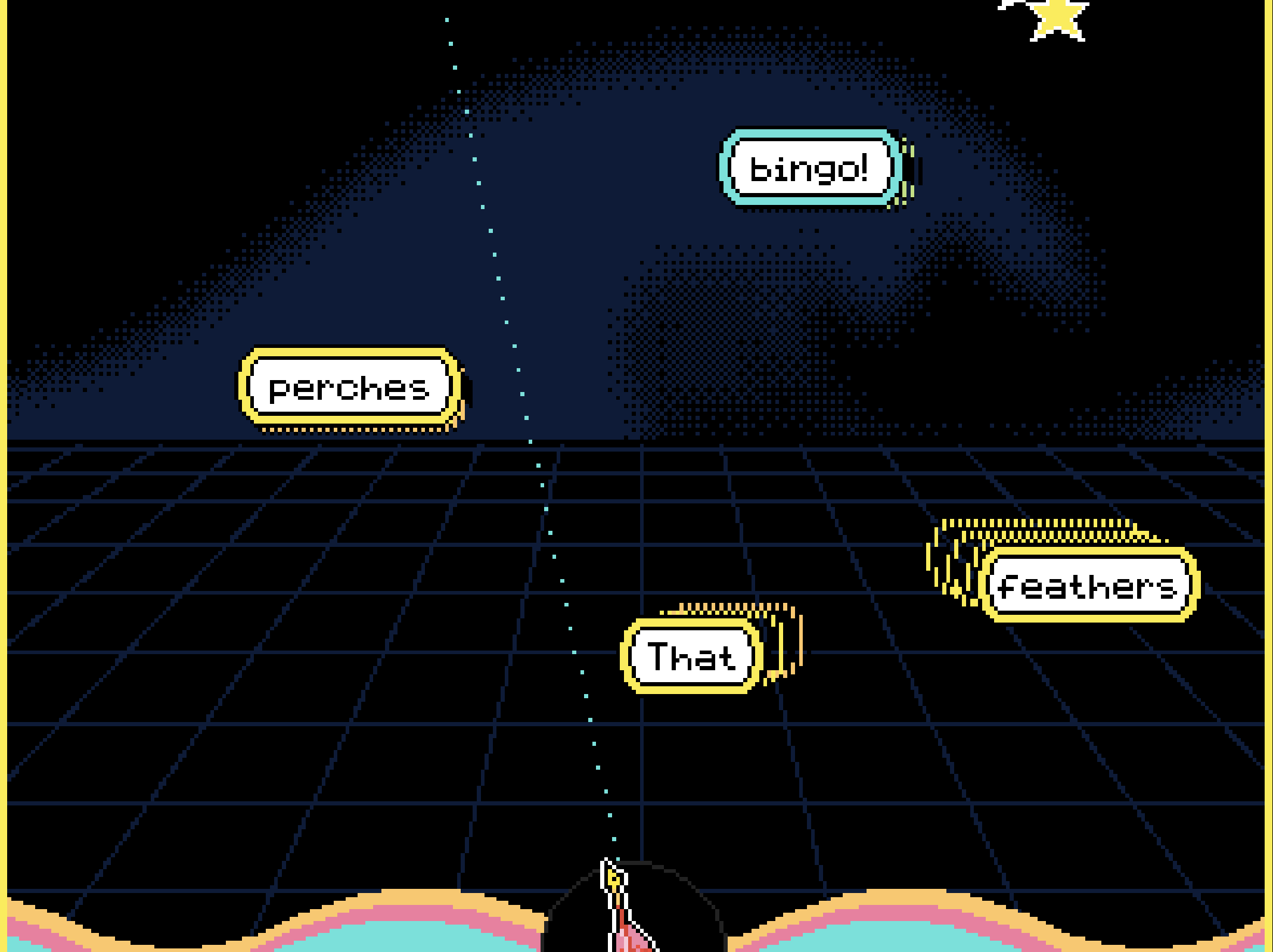

Directly inspired by games like Math Blaster! and many of the 1980s various ‘edutainment’ computer programs, Emily Blaster is a simple three-level memory test that starts the player off with some easy instructions: read the lines of Emily Dickinson’s poetry before the level starts, then shoot it in the correct order when it lazily falls from the top of the screen. (Of course, there’s some stars for extra points.)

The game is cutely stylized partly after the book’s color scheme and partly after Emily Dickinson, with the “blaster” being a feather quill. In between each of the levels, some great recommendations for the book come from names like John Green and Erin Morgenstern, author of The Night Circus. When the levels are completed, the player receives a score out of three stars and a corresponding “level” that determines your skill. As a single-star-earning noob, my title was the disgraceful “Poetaster,” an “inferior poet” according to Oxford.

As Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow follows a computer-programming duo through decade-long highs and lows of love and creativity, Emily Blaster is designed to be “convincingly something a clever college student might be able to make on limited resources and time in the 1990s.” An early game for the story’s titular character Sadie Green, Emily Blaster is the perfect example of the promotional and fundamental opportunities provided by simple meta tie-ins in other media. Rather than marketing to a sole demographic of readers, Gabrielle Zevin has taken the time to widen the appeal and reach of the novel using a completely different medium, a video game, presenting another angle of the same narrative. While this crossover occurred quite often in the past with movie-centered video game tie-ins, the increasingly modern expectations of a game’s abilities (and the cost to meet these) have far outweighed any demand or desire to return to this money-making method. Emily Blaster shows that the labor or product does not need to be intensive to simply gift its audience with a slightly larger piece of its world.

Play games, take surveys and take advantage of special offers to help support mxdwn. Every dollar helps keep the content you love coming every single day.